Rain continues today. Sanding and prep of the boat is temporarily halted. Which is fine. Something else must be righted now.

1. The story of the Boatman and the Lucky Penny

In 2009, the year she came of age, Mazie rode with Howie through Lava.

That trip for all of us was the high water mark of a magical summer. Not even twelve, Mazie had busked in Telluride, had run in the desert, and bank to bank she had swam the Colorado.

That trip for all of us was the high water mark of a magical summer. Not even twelve, Mazie had busked in Telluride, had run in the desert, and bank to bank she had swam the Colorado.

But in this particular moment, there was little glory to be had. The guides had nervously scouted the rapids and Mazie was well aware of their trepidation. One by one, the rafts had set off, but when it came time for Mazie’s boat, she refused to get in. She stood on the shore shaking with fear, and then in tears asking to be taken around some other way.

But there was no other way.

—

Lava sits in the depth of the Canyon, cut one mile deep in the earth. Here the precambrian metamorphic rock is hard and ancient, dating back 1.75 billion years. But the rock still feels fresh and scary and hot as if it was born yesterday. And yet it came into being before there was even life on earth. Looking at the chasm faces, you feel palpably that the world of life doesn’t belong to the ancient world that’s revealed there. And yet life is. The water cuts through the canyon, wearing it away until at Lava Falls water meets rock steeled by pressure and fire. Lava is harder. But in the end, minuscule grain by minuscule grain, the water will win.

—

To be safe at Lava you work against instinct. If you bull forward straight ahead, you go over the lip of the ledge and you end up in the hole which is where you don’t want to be. There water turns into a turbo charged washing machine the size of a small building. You get thrown around or held under, or perhaps spit out hopefully in one piece.

To avoid the ledge hole you have to bank right, straight into a chute that slams you dead against a rock face. You ride high and bank off the wall, careen around the hole into the mountain size waves that threaten to flip you back.

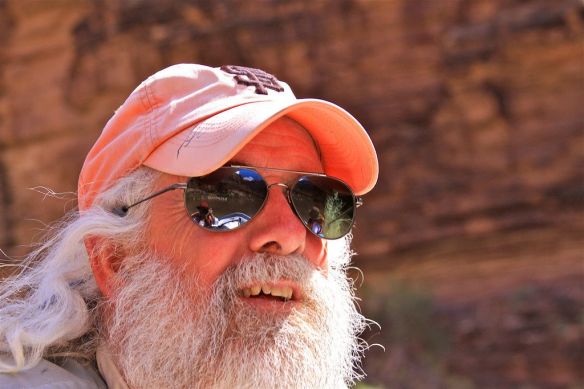

Howie has guided river trips on the Colorado for over twenty years. He has plenty of experience. But each time he runs Lava, Howie dons a white shirt and tie. It’s his schtick. You need to respect Lava he says. You don’t own it. That water owns you.

Howie has guided river trips on the Colorado for over twenty years. He has plenty of experience. But each time he runs Lava, Howie dons a white shirt and tie. It’s his schtick. You need to respect Lava he says. You don’t own it. That water owns you.

Mazie had chosen to ride with Howie on this run. She loved his humor, how he told a story about ancient Puebloans, narrating it with tiny plastic figures, until folks realized he was making things up. He had been on the river for twenty years. But most importantly, his collected and calm manner was equal to his experience.

—

Mazie stood on the shore sobbing, refusing to get in the boat, begging for Howie not to leave the shore. All the other boats, including ours had already left. Howie was alone and at a loss. He had no children of his own and had no experience about what to do with a terrified little girl. So he improvised. Before he untied the boat he knelt by Mazie and put something in her hand. This is my lucky penny, he whispered to her. I’ve carried it every time that I’ve gone through Lava. Hold it tight, he told her. Hold it tight and it will keep you safe through the rapids. With that, Mazie climbed into the raft and she held on.

Mazie stood on the shore sobbing, refusing to get in the boat, begging for Howie not to leave the shore. All the other boats, including ours had already left. Howie was alone and at a loss. He had no children of his own and had no experience about what to do with a terrified little girl. So he improvised. Before he untied the boat he knelt by Mazie and put something in her hand. This is my lucky penny, he whispered to her. I’ve carried it every time that I’ve gone through Lava. Hold it tight, he told her. Hold it tight and it will keep you safe through the rapids. With that, Mazie climbed into the raft and she held on.

Mazie clutched that penny. Twelve years old, not even, and she descended into that roiling water with Howie at the oars. They struck deep, disappeared, emerged and struck deep once again, the boat fully disappearing beneath the water. They shot out into the face of the waves that mounted again and again until they were at last carried through.

Once all the boats had safely made it, we tied up against the cliffs towering above the water. Shaken, giddy, and fully spent, everyone had stepped onto the ledge to which we were tied. People sat and rested, some drifting into sleep. Mazie, though, stayed in the boat, sobbing forever it seemed, still afraid to let go of the lines. One by one the boatmen sat with her. Howie held her, letting her know that they were safe, that everything was okay.

—

A few days ago, Howie Usher suffered a severe stroke. He was set to go down on the river this summer. There’s little word yet on his condition, only that it’s bad and that he has a difficult road to recovery. This time the water carried wrong. Howie went down over the lip and he’s in there now. Things didn’t go right. And now Howie against his will, knowledge, and experience, has been swept into the hole.