In broad strokes:

We’re set on a low ridge about 18 miles inland from the ocean. We’re high enough that the ridge holds back the maritime fog and moisture, yet close enough to the coast that we escape the summer heat of the valleys to the east. There’s lots of water. Artesian springs seep out all along on this slope, while atmospheric moisture rides in as fog most mornings.

The San Andreas fault – that neat crack marking where the Pacific Plate abrades against and is peeling away from the North American Plate runs just to the west of us. Coming down off the ridge, you can actually see the gash in all it’s violent beauty. You can even drive into it. As you approach the coast, the rounded hills bunch up like crumpled tissue. As you push out you emerge into the narrow strait of Tomales Bay where the ocean has seeped into the San Andreas. Just across the water rests Point Reyes, slowly calving away from our continent at a pace at which we can actually feel it. I hid out there last month, and from the rocks at dawn I watched the tidal pull and stared back at that old land from which I was then receding.

By another designation we’re in the Green Valley sub designation of the Russian River appellation. We have soft sandy soils. The cool moisture and the more moderate temperatures make us good for Pinot and perhaps Chardonnay, though I don’t know much about that.

Just to the south the ridgeline gives way to a wide channel that draws the moisture inland from the Pacific toward Petaluma. That swath, buffeted by cold winds in the winter and summer, is marked by high undulating grassy hills best suited for dairy and grazing. In the spring it looks a bit like Ireland. That’s where you find loads of goat farms, Bill Niman’s beef, Straus milking cows, the Cowgirl Creamery and a wide range of artisinal cheese makers.

But where we are to the north it’s considered the banana belt – a perfect marrying of temperatures that near anything can grow here. Luther Burbank’s original farm sits about two miles to the north. There he developed hundreds of new varieties of apples, stone fruit, cacti, vegetables, ornamentals and what not. He supposedly thought it was the most perfect growing environment in the world. The land we sit on has grown cherries, prunes, plums, apples. It can support Meyer lemons and blood oranges. Figs and olives and grapes and walnuts. Peaches, nectarines, lettuces, winter brassicas. California oak acorns and redwoods. You name it.

And by yet another designation, the north of us is home to a vestigial group of Algonkian speakers – Yurok and Wiyot left over from the ancient middle incursion onto the continent. They most likely stayed put on the coast while their relatives pressed onward to the east, ultimately populating the entire eastern seaboard. The Algonkians are surrounded by a once heavy population of Athabascans – later arrivals from the third migration. They had come down from the Alaskan interior and the Arctic circle, having left their Inuit and Yupik cousins sometime way back. Resourceful opportunists they filled in the territory in north eastern California. Their De’na relatives pushed further, of course, down into Idaho, Colorado and the Southwest. To the south and east of us, it’s mostly Uto-Aztecan, the domain of the Paiute that ranged into the Sierras along with many of the central valley Sonoran tribes: Colorado indians, the Chemehuevi, Mojave. Some were Quechuan. But most, like the folk down south on the coast – the Kumeyaay, Diegueño, Cahuilla – are mostly cousins of the Puebloans – all folks left behind on the great historic primary migrations from the south.

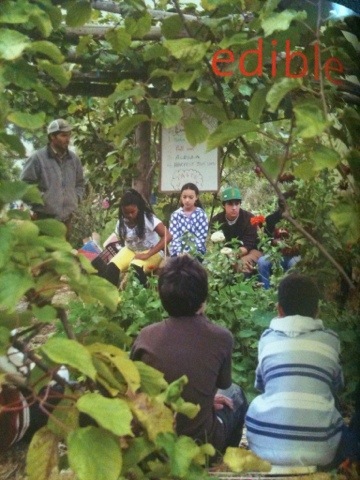

As for us, we’re living on Pomo and Coastal Miwok land. Back in the day, winters were spent on this ridge line where we now live. In the summer, families and clans settled on the perimeter of what is now called the Laguna de Santa Rosa – the enormous seasonal estuary that extends from Petaluma and the Bay tidal marshes all the way up to the Russian River and Dry Creek Valley. The lagoon is the heart of this place. In the summer, the flat oak studded grasslands extend across the valley to the Mayacama mountains and the delightful hump of Mount St. Helena. In the winter, the tidal reach and flooding extends right up the valley, inundating the land near to the Gravenstein Highway. The lagoon is rich land. Our food comes from there. Literally. For the time being we get our veggies from Laguna Farm – a group of industrious folks who have intensively planted a small area on the edge of the lagoon. Right now we’re getting radishes, kales, chards, brussel sprouts, broccoli, an abundance of salad greens, carrots – most of it hauled out of those wetlands or the areas planted on a knoll adjacent to our house.

I was born in California. It’s my native land. And now after decades away we’ve returned as Californians. I explain to my daughter that this ultimately is the place which we are from. But we also return as guests of those residents that preceded along with all those energies still present. In the morning after the fog burns, I look out the window. The possibilities are manifold. The world sparkles in all it’s glorious frission.

Once upon a time on a living room table in Pasadena, the Nowruz goldfish swam in their small bowl. They had been brought into the house as a harbinger of the New Year. But did they know why they swam in the bowl? Or even that they were they and that they swam in a bowl at all? Did they know they had meaning? That they were living fire in a globe of water and the embodiment of spring?

Once upon a time on a living room table in Pasadena, the Nowruz goldfish swam in their small bowl. They had been brought into the house as a harbinger of the New Year. But did they know why they swam in the bowl? Or even that they were they and that they swam in a bowl at all? Did they know they had meaning? That they were living fire in a globe of water and the embodiment of spring? Once upon a time we drove to a shabby boulevard in Westwood in a heavy downpour to purchase saffron, halwa, flat bread, jordan almonds, pistachios, whole fish and tea. The rain was so heavy that the freeway traffic on the I-10 slowed to a crawl and it was as if the world had become cemented with water and we had returned to our amphibious selves.

Once upon a time we drove to a shabby boulevard in Westwood in a heavy downpour to purchase saffron, halwa, flat bread, jordan almonds, pistachios, whole fish and tea. The rain was so heavy that the freeway traffic on the I-10 slowed to a crawl and it was as if the world had become cemented with water and we had returned to our amphibious selves.