Another sleepless night that came upon sleepless nights upon sleepless nights.

Bottom feeder motel.

Sparks, Nevada.

Bobby pins and a stray pill and bits of toilet paper stuck to the bathroom floor. Faceplates stripped from the outlets revealing crumbling drywall. Outside in the cold white glow of the street lamps the lot was bursting with a mass of semis. I was awake at two and three and four in the morning. I did Duolingo for an hour. And then I doom scrolled. And then I listened to an Apple Fitness+ Sleep Meditation. And then I counted sheep.

At six I relented. In the darkness I went down to the foyer to survey the America’s Best Quality Inn complimentary breakfast. Individually packaged chunks of dough that were supposed to be bagels. Minute Maid orange juice. Prepackaged muffins. Brown envelopes of instant oats.

I rummaged about. A couple joined me. She seemed impossibly young – A waif like girl who appeared to be no more than 15 or 16.

Her boyfriend, older, shuffled about, shifting gaze and indifference. They gathered up a stack of muffins and bagels and butter and jam. What was their story? Why here? Why in this hotel, right now? I kept sneaking glances. I wondered if she was being trafficked. It would make sense. Take a bus into Reno and right away, volitionally or not, you set up shop. But why Sparks, a good ten miles out of downtown? I watched them, but I said nothing.

We sense. Sometimes we may even know. But we fail to answer.

And in that way my averted gaze became my own private complicity.

I emptied the oatmeal into a paper bowl and added some water from the sink. I placed it in the microwave. And with those dry cinnamon oats the morning began.

A neighbor in our small town in the Bay Area had invited me to travel with him to Reno to knock on doors. In the Vietnam days he had been a student in the seminary and he had been inspired by the Berrigan brothers to be an activist priest. He had dropped out because he felt he was gaming the draft, and so instead he had written to the Board and had declared himself a conscientious objector, in effect inviting them to throw him in prison. His whole life he had believed in something that he called peace. He was a vegetarian and drove an electric car and believed in the electoral process.

I, on the other hand, was still traumatized by my last canvassing venture in 2016 when my family and I had knocked on doors in Sparks, Nevada and had encountered no small amount of vitriol and frustration. And then of course there was the outcome that year. So I had intended this time to stay home and help cure ballots by phone from the safety and quiet of home, but our neighbor’s call came the day after Bezos had prevented the Washington Post from printing an endorsement. Oligarchs muzzle the press and in that way we all begin to obey in advance. It was incumbent upon me, I decided, to place myself in a public space and declare my values and allegiance despite whatever I might encounter.

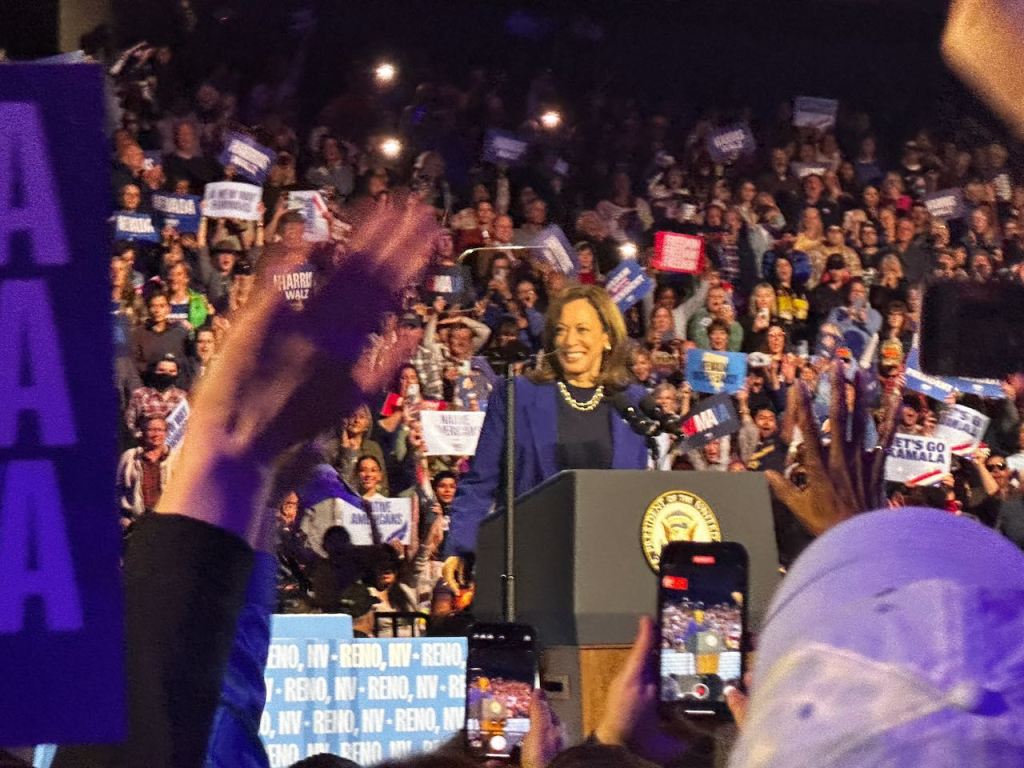

Rolling into Reno on Halloween afternoon, we’d learned that Kamala would be speaking that very evening and so we headed straight to downtown and parked outside a dilapidated pawn shop (Jewelry! Electronics! Guns!) a stone’s throw from Circus Circus and a block away from the bus station that seemed to be trafficking in its own comings and goings. The line to the arena stretched six blocks in the vacant downtown, but it moved quickly and a festive and gentle camaraderie filled the air. I’m not one for rallies, but in this moment I was grateful to feel embraced by the fold. It felt like America, or at least like my imagined idealized America. Young. Old. All manner of complexions, a Whitman like concert of body and belief, migration and experience coming to celebrate not just our commonality, but the delectable variety of our difference, and what a joy it was to learn from and to revel within those very things that made us different. The head of the Nevada Dems asked us to imagine a moment in January, on the steps of our capitol when a Black woman named Kenji Brown Jackson, herself dressed in black, would hold in her hands the bible of Fredrick Douglass and across from her a Black Asian woman, dressed in white, or perhaps even in a tan suit, would place her hand on that bible and swear to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.

And then more speakers, the female mayor of Reno, their Senator Catherine Cortez Masto, and then Kamala herself entering to the beat of Beyonce’s Freedom.

This was my America. Not a Christian nativist one, but instead multivalent America that I so badly wanted to believe in.

After the rally we returned to the car, famished. We stepped into a pho restaurant. Outside, a couple — a white woman and a black man — sat on the sidewalk, both unwashed and shaking and twitching with the jitters, jonesing it seemed, but instead asking for money for food. My friend gave them a bill and they cackled.

The following day.

Coffee hour with Deb Haaland, the Secretary of the Interior, born in the San Felipe Pueblo and who once struggled as a single mom, now stumping in jeans casual at a Native run coffee shop in downtown Reno. The sleek shop of Star Coffee was filled with a dozen or so Paiute and Shoshone, and a Blackfeet fellow who was apparently a big actor. All young, all activated. They were set to canvas in the rez towns one to two hours outside of Reno. The towns were rural, so culturally they sometimes trended red, voting in synch with the dominant non-native culture. And some might even have shared common sentiments, feeling ignored by urban centers and elites and governments that felt long on promise and short on delivery.

Later that day at the canvassing headquarters we were set up with the app. I stood next to an unassuming woman in jeans who introduced herself as ranking Senator Patty Murray. I had voted for her 30 years ago when she first ran for Congress in the state of Washington. She told of how she was no stranger to door knocking. When she first ran, knock on doors she did. One resident had even announced that she was going to vote for her because she clearly really wanted the job.

It was a different kind of canvassing now, however, even far different from eight years ago when we walked the suburban streets of Sparks with sheets of paper in our hands, checking off addresses and names. Here we were given an app that displayed a high res map with precise locations of each Democratic or Independent voters who hadn’t voted yet. We had names, age, gender, party affiliation, address, phone number.

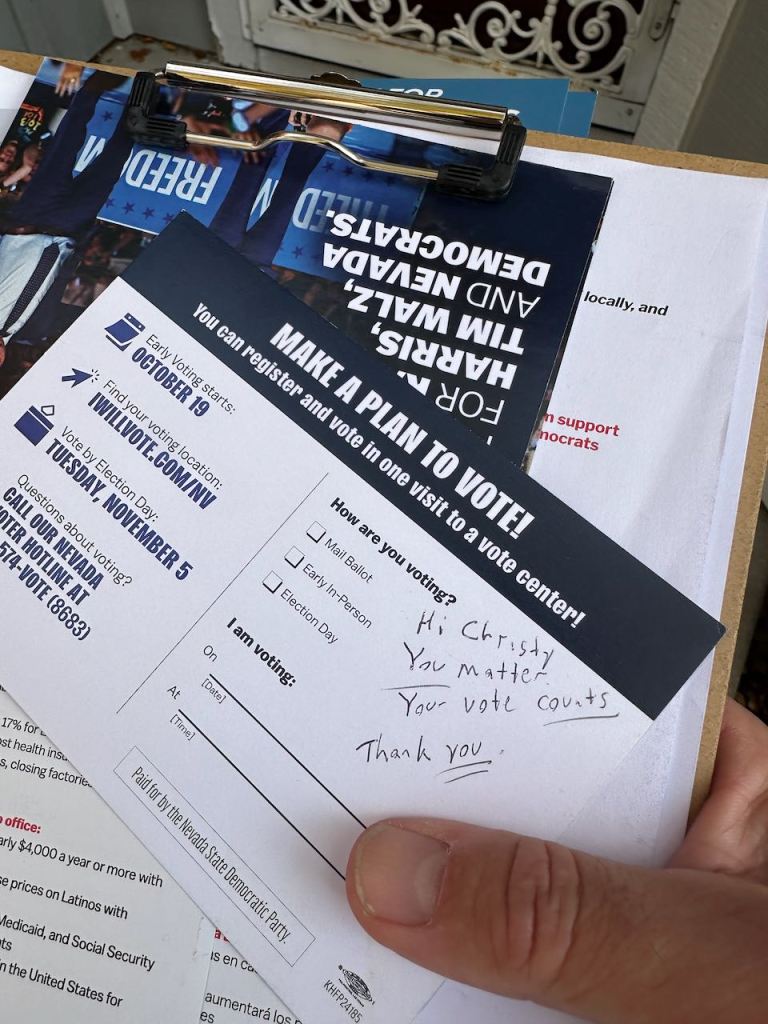

Our process shook out pretty quick. We’d drive to a house, hop out of the car, run up to a door, knock twice, and if no one answered we’d leave campaign literature. I took the time to write a small inscription on the Voting Plan card: “Hi ____! You matter. Your vote counts. Thank you for making a difference.” Smiley face. Then back to the car, drive a few houses or few blocks and hop out at the next house.

The neighborhood: upper middle class suburban, nearly all the houses armored with ring door cameras. Many of the porches still draped with Halloween cobwebs and plastic pumpkins and plastic decorations soggy from the recent rain.

We saw few people that afternoon, but if we encountered a live person, we engaged. We’re canvassing for Kamala, we told them and we encouraged anyone we saw to vote. One woman with a British accent crossing the street told us she had just returned from Europe. The whole world was watching, she said. Europeans are sick to their stomach over this election, terrified of what would happen if he was elected. We are the strongest economy, the strongest power, the greatest country on earth, she said. And he’s completely undisciplined, non functioning.

At one house a man answered. It was dinner time and his kids were clamoring at his legs. We complemented him on his red Model Y. He worked at the Gigabattery plant, he said, designing new state of the art batteries. It was a nice spacious house, well appointed, two EVs in the driveway. They had good jobs, they had done well, they had both voted. He lamented over how far off the rails Elon had gone. It was the reason he had quit Tesla, and he described how even back in the day Elon would manage through fear and intimidation. He had only grown more mercurial and erratic. But then our voter reminded us that there were a hundred thousand people employed building Tesla cars and batteries. They were good people working hard in good jobs. We can’t throw them under the bus, he said.

We came to an address where all the facing and flanking houses were staked with the armature of Trump Vance signs. We knocked on the door, seeking a woman, registered Democrat, in her late fifties. She opened the door. When she saw we were with the Kamala campaign she ushered us in. Well curated art on the walls. Piles of clothes in the foyer. They had been in Venice for the Bienale, she explained. They had come back the previous night so that they could vote. Her husband was a professor of history. She worked in an escrow office. We asked her how she contended with what was around her. She said that just walking out her door depressed and scared her. She felt under assault. We’re Jewish, she explained. My husband studies European history. We know where this kind of anger and vitriol leads. How can people not know? She asked.

We left. It was dusk. The mood felt desultory and autumnal, as if I was canvassing on a darkening street while a hooded psychopath pursued Jamie Lee Curtis with a gleaming knife.

Dinner. At the canvassing headquarters a young woman had directed us to a pizza place in Midtown Reno. Thin crust, house made pasta. Our waitress was in her twenties, young, hip, warm and bubbly. We asked if she had voted and she smiled broadly. Oh yes, absolutely, she announced. I was relieved for common ground. I won’t ask how you voted, I said, but thank you. We have to win this one, I said. Absolutely, she said. Later when we asked for our bill, we asked how she was feeling. She smiled and stammered and said she didn’t know. I’m feeling super hopeful, she said.

Are you prepared if it doesn’t turn out well, if she loses?

Oh no, she said. I’ll be feeling really really happy if she loses, she said. She beamed broadly and laughed, giddy almost.

Wait. You voted for him? we asked.

Yes! she announced.

But why? What do you see? we asked. And then she said something about believing in life.

Back at the motel, the hallway smelling of dank, a young kid stepped out of his room and wandered down the hall, wafting about him the smell of weed. As I fell asleep I thought of our young waitress. She was kind and approachable. I wanted to go back. I wanted to talk with her when she was off the clock. I wanted to ask where she got her information. I wondered if perhaps she was a fundy, perhaps she went to a mega evangelical church and her pastor had simply told the congregation how to vote. But even then, what was her world? What was her life and her understanding of the world that prevented her from seeing and hearing the things that I and so many people saw and heard?

At three I awoke into my now customary restlessness. I considered the previous afternoon and the tea leaves of the canvassing app. In that upper middle class neighborhood, we were directed to perhaps only one out of every twenty or thirty houses. Sure, many households may have already voted, or they were registered Republicans who had turned their votes toward Harris. But overall it felt to be exiled in the winderness. The size and quality and build of the houses improved as we ascended the hills. At the top of one knoll stood a veritable walled faux Italian hill town with its own heavily reinforced medieval gates. Here among these rarified palazzos we were directed to only one door before descending.

And there was more. The majority of the names on our list were women in their mid twenties to mid fifties. We’d knock on a large house, but there was only one registered Democrat. A woman. Had her husband already voted? Or was it a split household? At more than a few houses, a man answered the door. When we explained that we were looking for his partner he would grow impatient. He would take the campaign literature and say that he would give it to her before he shut the door. Those warm notes I’d been writing? In effect I may have been outing these women, exposing them to some not so gentle retribution that might come their way.

I got out of bed and stared at the parking expanse filled with semis lit by the garish white glow. In this dim hour I thought of the 16 year old girl from the morning before. It made sense now, as if a nation entire was being trafficked.

I thought of all those people who had permission to enact violent language or even actual violence. It was permissible, even anodyne, those Trump Vance Helvetic san serifed signs. The font of corporate office parks and suburban strip malls. Anonymous and inoffensive, a font used to render modern horror (Exxon, Microsoft, Google, America’s Best Value Inn) into the safe and banal.

The following day we showed up at HQ for the Washoe county Dems and were dispatched to a sprawling low end apartment complex the size of a small town. The synthetic siding was worn, the cement staircases dirtied and pocked with black gum. There were no Ring cameras or even peepholes here, just flimsy doors with cheap pewter knockers. From this complex you could look up to the hills in the southeast, to the upper income neighborhood we had canvassed the day prior.

Most doors went unanswered as we searched our way through the warren of addresses. The names trended Hispanic with some Anglo or Middle Eastern. Even at eleven, it seemed a lot of people were still waking up, a reminder that casino towns run hot mostly at night. When doors opened, we caught glimpses of cluttered apartments.

When we encountered the Hispanic non-English speaking families I felt hopeful. Their bearing felt aspirational. Many people bunking down together, working hard, some sending money back home, perhaps dreaming of getting ahead. It was the other native born couples in their 60’s and 70’s that worried me. What did it mean to perhaps work your entire life and to end up in a dilapidated housing complex?

At one door, a tall young African American man answered, a pug nuzzling at his feet. We asked for a girl’s name. Yeah, he said, and he called her forward. We asked if he had voted and he said yes. A young black woman, early twenties, sweats appeared at the door. She called for her dog French Fry to stay inside. She had tears on her cheeks and she apologized. I cry when I wake up, she said. We asked if she was voting and she stammered. You know, she said, I’ve..I’ve never voted before. This is my first time…” she smiled, embarrassed. I burst with excitement. You don’t know what that’s like for people like us, I said. A real live first time voter! We encouraged her and asked what she liked about Kamala and she went to reproductive rights and then protection of women’s health. This perhaps was what it looked like as a semblance of political consciousness was being born. She couldn’t believe that the other guy could have felony convictions and still be running when someone like her would have gotten a shot.

I noticed again the tears on her cheeks. Are you okay? I asked. She smiled. Yeah, she said. I’m okay. Sometimes I cry when I wake up from a sleep.

I offered that her vote, that her voice was far more important than mine. That she mattered. That her voice mattered. We gave her directions to her polling place. We thanked her and we asked her to thank her boyfriend and French Fry for all of them being so generous with their time.

At one house a Latino man answered. When I asked, he said he preferred to speak in Spanish. He confessed that he was worried. He said he had his ballot and other people in the household did as well. He offered us water.

At another house, a young man answered, appearing still to be waking up. The people we were looking for weren’t home, but they had their ballots. We asked about him and he said he couldn’t vote, but the other folks, they had their papers he said. We bumped fists. Thank you for your work and your kindness, I said.

Exhausted by early afternoon we walked back to the car. A large bellied man stood in front of the bed of a truck, unloading cases of beer onto the patio of his apartment. “You with Trump, he slurred. We walked on. His face was flush and he staggered. You with Trump? He asked again.

We answered that we were knocking on doors for Kamala.

“Fuck you,” he said. “Fucking camel tongued camel toed bitch,“ he said. A middle aged sallowed complexion woman sat on the porch smoking. She leered at us mockingly, as if we, whoever we were, were at last going to have our comeuppance. Fucking bitch, he said. I doubted that he was a member of the engaged electorate, instead mired by fate or misfortune in the cheap seats of this Bread and Circus.

I felt saddened. I thought of NAFTA once heralded by Democrats as promising an economic boon. I thought of the millions of jobs exported, gutting small towns across America, how we would transition to what was once called a “service economy.” I thought of the peddling of cheap foreign made products from big box stores, of the gutting of Main Street, of the consolidation of our economy into the hands of a few, of populations rendered so low that there’s no reaching up and and instead left to pushing others down. We climbed into our car, and a truck roared past, the driver hurling invectives at us.

Rolling out of Washoe County we saw a troop of people on an overpass waving not American flags, but Trump flags, our national polity being reduced to loyalty to one man. I put a call out to my brother. Mostly unhoused, he spends much of his time pacing the streets of downtown Santa Cruz.. We try to speak most days. My dear brother has seen such darkness that his eye is as clear and unvarnished as any can be, his humor as dry as dust. On this day he was concerned because the cliffs fronting the Santa Cruz neighborhoods were collapsing against the rising sea. He called it euphemistically, “the hole in the sidewalk.” And then there was the initiative to ban sugar that was tearing the community apart.

The world thinks it has problems, he said. But they have no idea what grave catastrophes are facing our hamlet.

Before we hung up, I asked him to look into America’s Best Value Inn in Sparks Nevada. Can you see if there’s any correlation with human trafficking? I asked.

He paused. I can tell you absolutely yes, he said. As far as I know the entire I-80 corridor is a conduit for sex trafficking, he said. But I’ll look into it, he promised.

We left Washoe County and headed back up east into the Sierras following the fateful path carved by the Donner Party 175 years earlier.

Heading over the pass, a truck pulled in front of my friend’s Tesla, and he coal rolled us, spitting a black cloud of smoke in our windshield. We buy EVs to do good world for the planet, while another mounts himself in a black smoke belching truck to signal that he doesn’t believe in climate change and he resents the elites who champion it; and all the while, the hydrocarbon industry donate a billion dollars to the MAGA campaign, and the richest man in the world who made fortune on transition us to a clean energy economy, pimps himself just so that they can all be at the table. And meanwhile here we are feuding over vehicle preferences. More bread. More circus.

In three days we would hold a National referendum. I thought of the young crying eyed woman who would be voting for the first time and of how I had encouraged her, affirming so strongly that her voice mattered, knowing full well that Washoe was one of those counties primed to not certify the election. All sorts of electoral stunts were already planned to slow certification. And then there was the possibility that he might even win, that 60 million voters would not so much be disenfranchised, but instead merely left on the way side.

As we drove home I was left to consider the improbably strange history of America. Of our diversity of who we are. Of the nature of disenfranchisement and disengagement and the grave paradox of renewal. And we tell ourselves even now to hope. Because hope, that most American of sentiments, may be all that we have in the face of it.